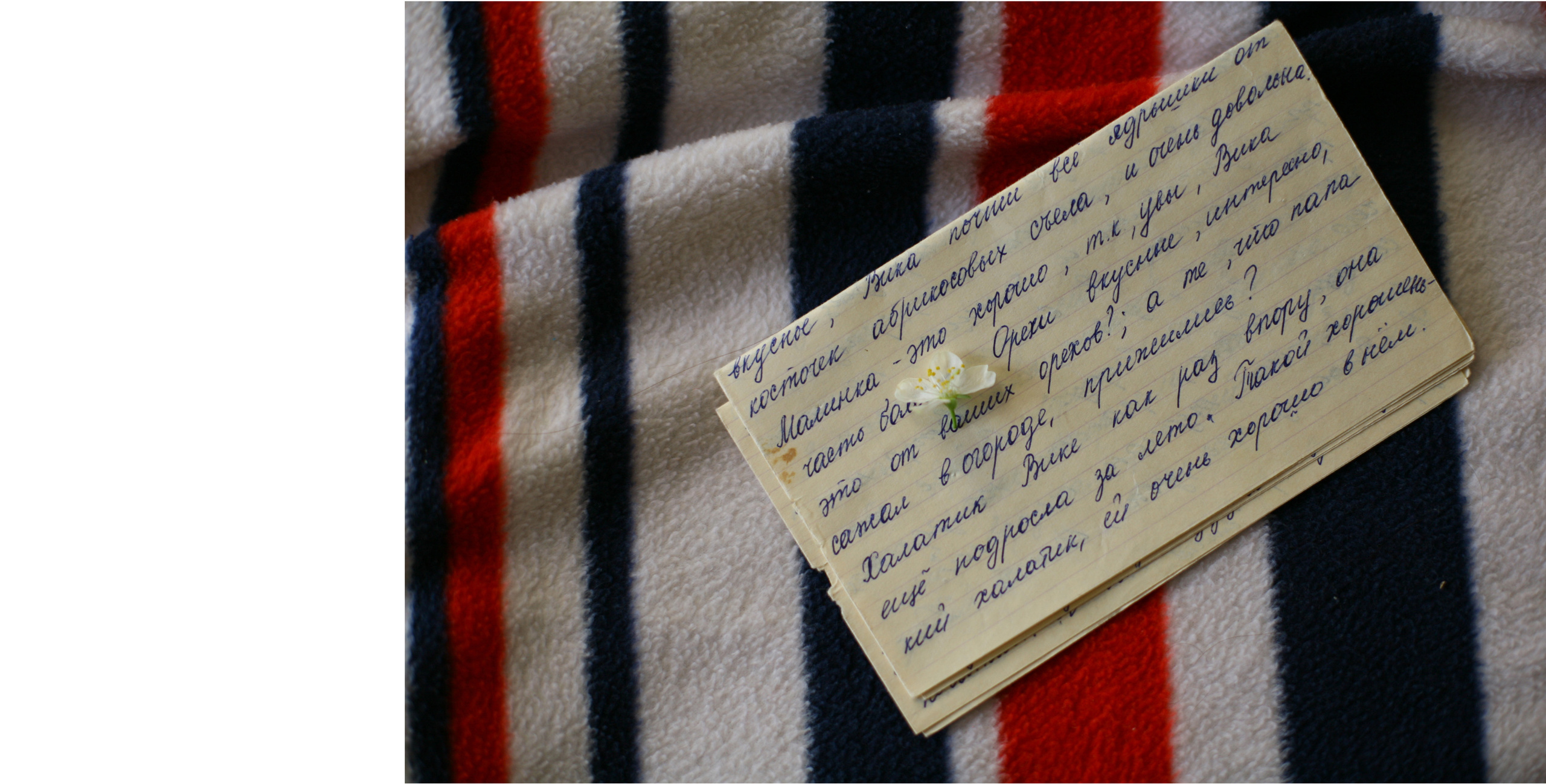

Mom’s letters

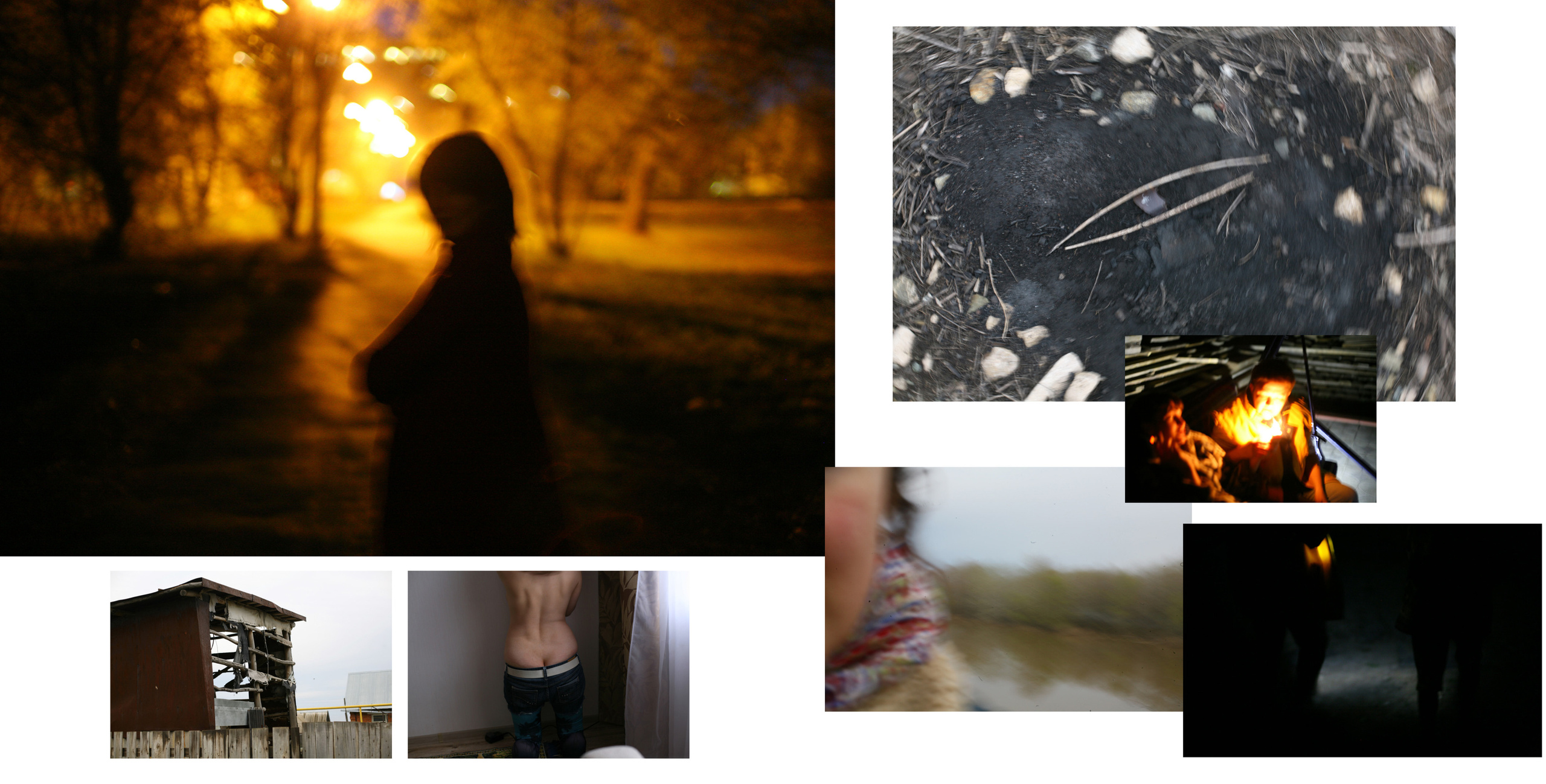

to my mom Natasha and my foster country Russia

My mum died when I was sixteen. She never turned forty. I’m forty-two now. I’m older than her. I outlived her in every way.

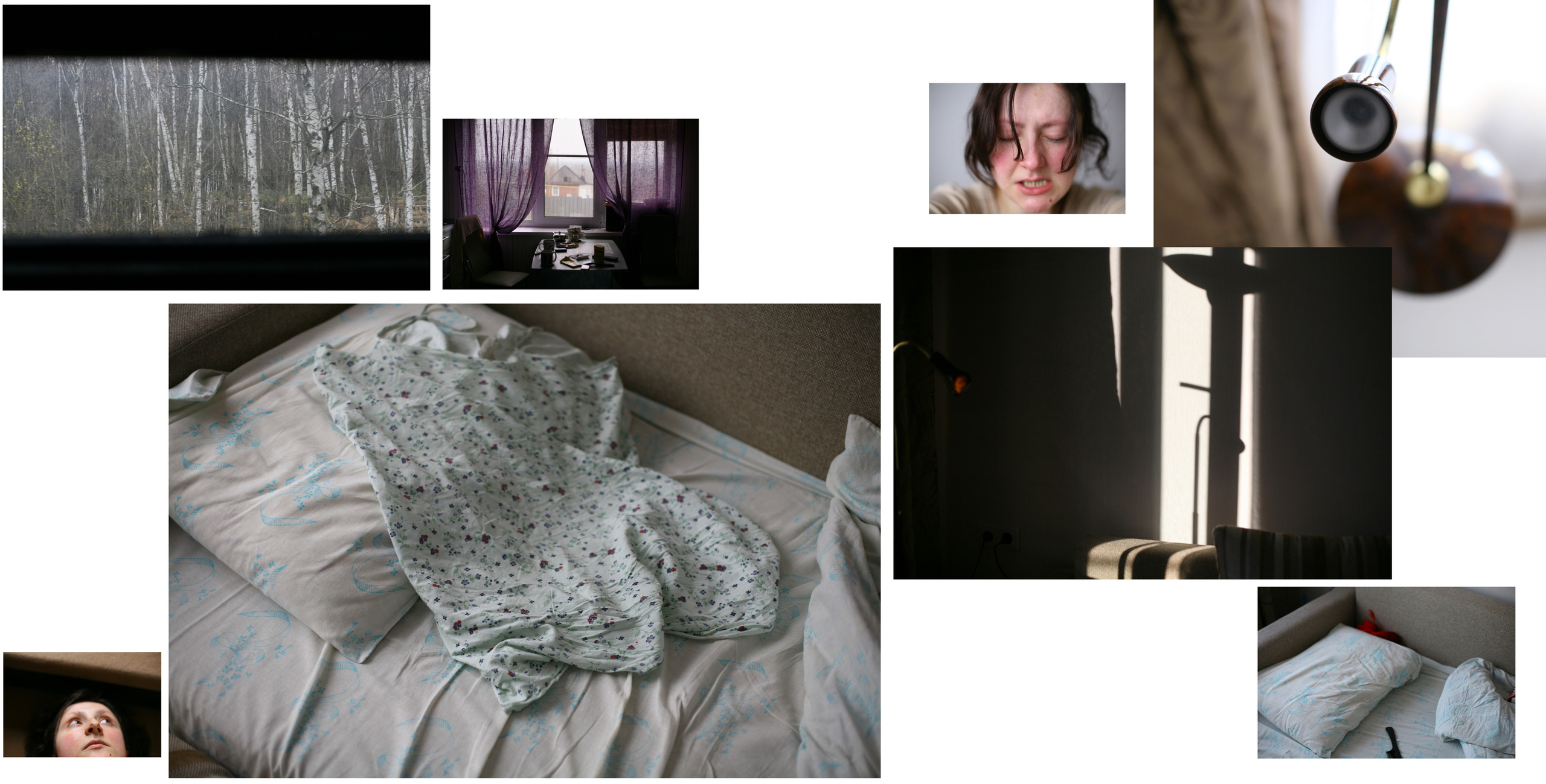

I have almost nothing left of her. A few letters. A stack of photographs. A handbag. A red notebook. Two rings, one of them a wedding ring. The slit of her eyes, her physique, the veins showing through. And a handful of memories.

Memory number seven. On the train, you give me your notebook and teach me how to draw five-pointed stars correctly, without breaking off. In the fifteenth year of your death, I’m travelling with this notebook in a Samara-St. Petersburg boxcar, back home, to a city you’ve never been to — but dreamed of visiting. You also dreamed of reading The Master and Margarita, but you never did. I live in the building where the TV series was filmed. It’s not a nice flat. Things outlive us. Things don’t remember anything. I remember my film — not you.

Memory number eight. How she — how you — stand at the window, tangled in the tulle, thinking it’s a door, trying to get out. Several months until the end. Illness bogs down the mind like static.

Memory number eleven. I paint you in your coffin. Too bright.

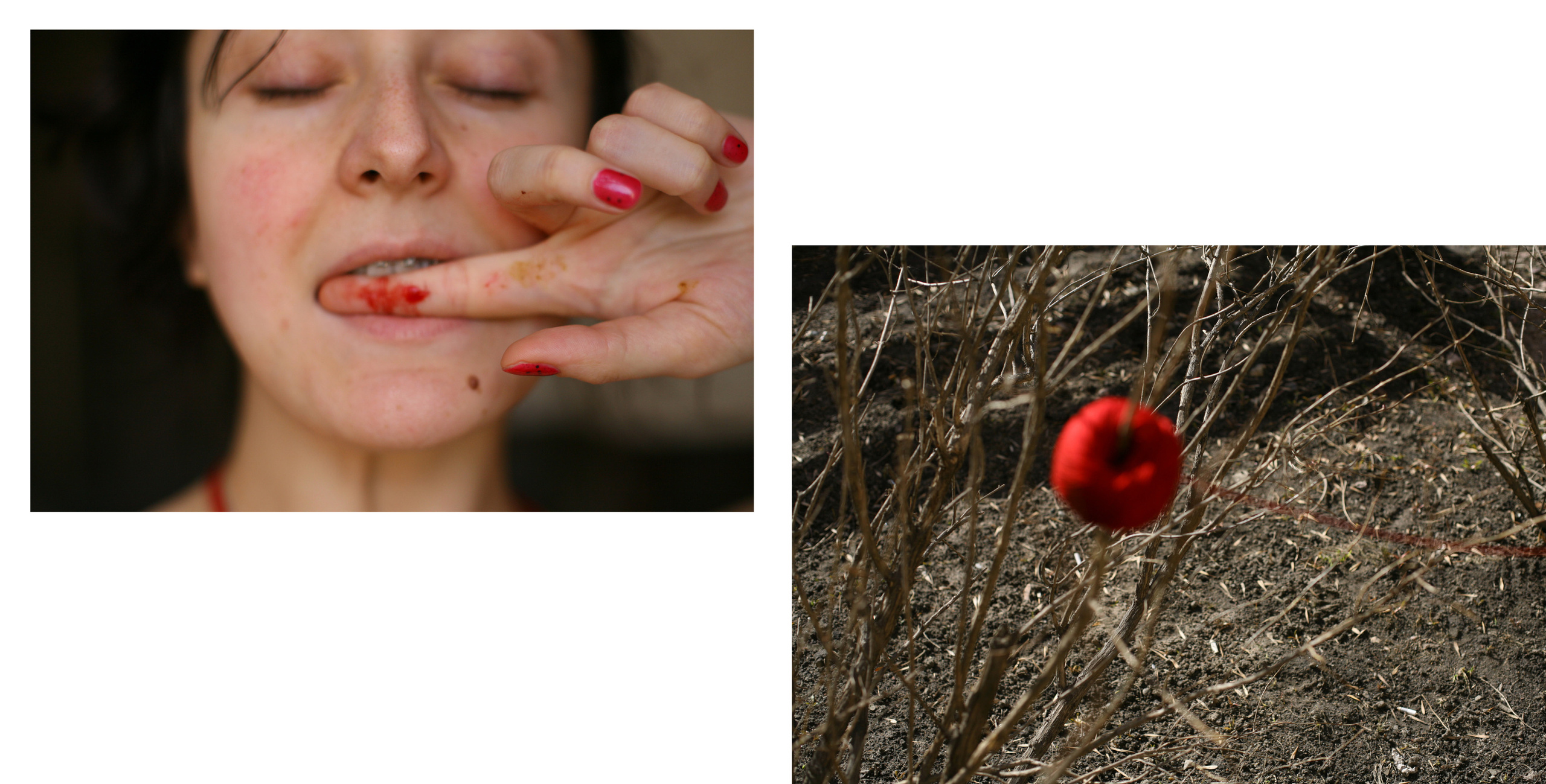

Memory number twelve. Girls’ day for the two of us, facemasks, me giving you a manicure. You open your wardrobe and shyly say, “Ladies don’t wear that”. And you want to look like a lady.

Memory number one. Your husband and my father banging my head against the fridge, drinking the leftovers, pulling up my T-shirt, putting his lips on my nipples, while you had already left the kitchen and closed the door tightly.

Husband, daughter, foreign city. Breast cancer, died at home. No friends.

I tried to see you in the fog and finally talk to you.

In 2024, eleven years later, I looked at this project differently.

To call things by their proper names, my mother ignored years of abuse against me and was complicit — and this project is not just about my mother and the unphotographed sinister figure of my father. He forbade himself to be filmed — but I did it with words and a performance, later.

This project I shot in my thirty-one, and it was an attempt at conversation. I spoke to my father in a different way afterwards, by directly calling his actions by name. Here. I got no answers from the other side of the world, or from this one.

But I got a lot of feedback — ‘I had a similar experience’, ‘I was abused in my childhood’, ‘I was abused in mine too’. The replies are quiet, you don’t talk about such things in society, but to the person who has already decided to speak up first — yes.

Now I could see in it not only my personal history, but also the history of the country. For almost a year now, I have been living in England, not in Russia. In almost a year, we have been accosted only once by a drunken man: no aggression, he just wanted to chat. And more than once I heard a cold whistle-whisper-shout at a child, with swear words. Always in Russian.

This is a project about Russia, with its violence and ignoring of reality. It is what it is. And I filmed it honestly.

- The project exists in book form

- It participated in the group exhibition Photofaculty-54 among the best works (2013)

- Published in F-Magazine with author’s commentary (2014)

- Two of the project’s works were selected for the Diaries exhibition of the Loosenart project in Rome (2020)

Commentary on the project from 2014

It was a strange and generally mystical experience a year long.

It was a road movie in time, a journey through states.

It’s a way of connecting, both with her and with myself. It’s a way of stitching together all the fragments, all the shards. It’s a way of acknowledging the fragments for what they are.

And it’s therapy, of course.

This book was a way for me to understand a lot of things. To understand-feel. With it I understood which way of working is mine, I understood how the state breaks down into two streams — the pythian state, in which you go blindly and follow the pain, and the priest, who then interprets everything done — and there is always something to interpret, if the pain is really followed.

At the end of the year, while working on the layout, I suddenly witnessed how each of the pieces takes its place, becomes the only possible piece of the puzzle. About each shot I could tell what it was about — and when I shot it, I couldn’t at all, and I chose only by the power flowing from them — and by the charge of that power.

It was important for me to go down that road on my own, without consulting or checking. And I am absolutely grateful to my mentor Anna Fedotova for believing in me and supporting me.

I was shooting for almost a year, from September to May; I was totally intuitive. The film was me; I had to recharge myself, tune myself up, expose myself to certain solutions, put myself in conditions where and when a spark could strike. I immersed myself in memories, thinking about her and myself, touching things. Drove to the town of my childhood and her death. Felt a connection.

It wasn’t easy and smooth — it was like everything was in leaps and bounds, and before each one I had to pull myself together because the leaps were in pain. At one point I wanted to stop, I even thought of another topic for my diploma. But that same night I took off a new layer, a new twist, and things started to unravel even more.

I did not include old, archival photographs in the project. The specifics are unimportant — the touch is impossible — I have no connection to it. And at the same time it is there, that connection is in my very body, in my very cells, in my very thoughts, in false memories. It is only because of working on this book that I have learned completely new facts about myself and her past. Family legends, what was, what you remember. It’s all different. Facts are unimportant, it’s not about them. Staging is no less documentary than reporting. Reportage is no less fictional than staged. That’s not the point at all.

I feel a connection. The magic is there. There is no death. Time is non-linear. Yes, I want to erase that sentence now, because I feel uncomfortable with the pathos, but it’s all just the truth, and I can bear it.

The book isn’t over yet, I can see further bumps and bumps to jump through, and hopefully I’ll get where they lead.

It was extremely agonising for me to write this commentary on the work, but I guess that’s why it was worth it.

2012—2024